What Is Money Demand?

Money demand refers to the desire to hold financial assets in the form of cash by individuals or organizations. It’s important to clarify that money demand does not simply represent a desire for more cash (as everyone typically wants more money). Instead, it answers the question of how much financial asset one wishes to hold at a given time in cash form rather than in other forms such as bonds or stocks.

Example: Consider an individual who possesses 20 million VND in cash. If they plan to deposit 5 million VND into a savings account and retain 15 million VND for daily expenses, their money demand is 15 million VND.

Another Example: A company may hold $200,000 in cash but requires $500,000 to invest in a new project. In this case, the company’s money demand is $500,000. To meet this need, they may need to borrow or issue bonds, subsequently selling these bonds to raise the necessary capital.

What Drives Money Demand?

According to the insights of the legendary economist John Maynard Keynes, there are three primary motives for holding cash:

- Transaction Demand: Individuals and organizations have essential expenses that occur at varying times, necessitating a certain amount of cash for transactions. For instance, a household needs cash to pay for utility bills, groceries, and other essential expenses. Typically, as the economy grows, transaction demand also increases.

- Precautionary Demand: Individuals often keep a cash reserve to prepare for unforeseen circumstances that may arise in the future. This is similar to how commercial banks must maintain reserves to account for potential bad debts when borrowers may default.

- Speculative Demand: In the stock market, speculative demand arises when investors believe that certain stocks will appreciate in value in the future. Additionally, the demand for cash increases if individuals prefer to hold cash rather than riskier financial assets (like stocks or bonds) because they perceive those as having higher risk. Thus, money demand will rise when expected returns on risky assets decline or their risk increases.

What Is Interest Rate?

Interest rate is the cost associated with borrowing cash, representing the expense that a borrower must pay to a lender. However, from a macroeconomic perspective, interest rates have a broader significance. They represent the cost of money; in other words, the expense of holding cash. The more cash you hold, the greater the costs you incur.

Example: If at any given moment you need cash but do not have it, you may need to borrow money, which will require repayment of both principal and interest in the future. Therefore, the interest rate effectively represents the cost of holding cash at the present time, an expense you would not incur if you did not borrow.

Another Example: If you have a sum of cash available and invest it in risk-free assets such as government bonds or high-rated bank deposits, you will earn an interest or return. However, if you choose to hold all that cash in liquid form, you forgo earning interest on those funds. Thus, the opportunity cost of holding cash is the interest that you could have earned had you invested in bonds.

These examples illustrate why interest rates can be considered the cost of money.

The Relationship Between Money Supply, Money Demand, and Interest Rates

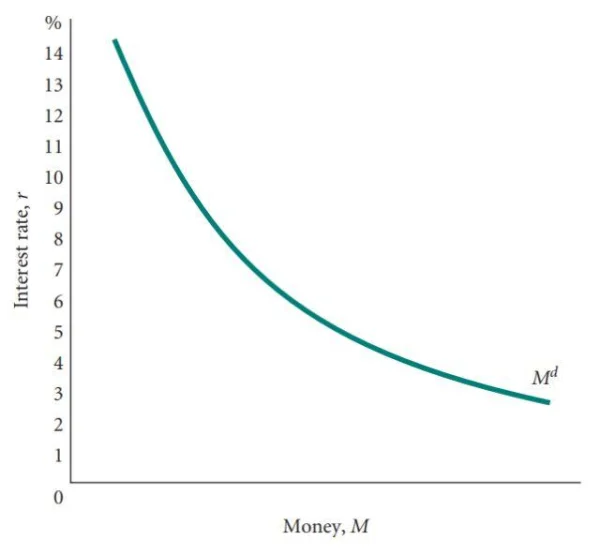

Similar to goods, when prices increase, demand decreases. The same applies to money: when interest rates rise (the cost of money increases), money demand will decrease. This is because individuals will be more inclined to invest, especially in safer assets like government bonds with higher yields, rather than holding cash.

Conversely, when interest rates decline, money demand tends to increase. Consequently, you can visualize the money demand curve as a downward-sloping line on a graph.

The Demand Curve for Money and Interest Rates

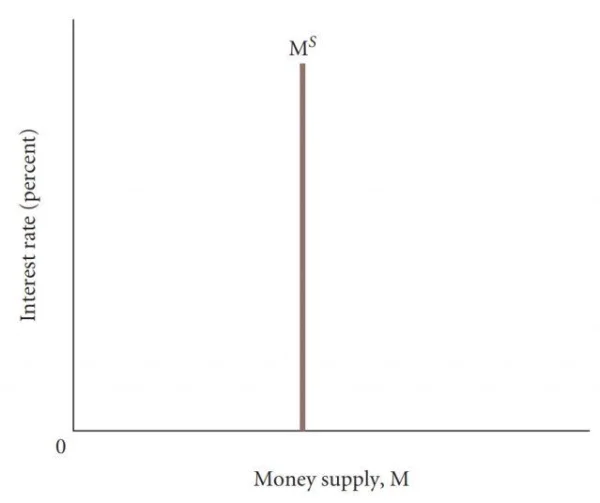

For money supply, central banks have the ability to control the money supply at will, regardless of market interest rate fluctuations. Unless there is a change in monetary policy, the money supply remains a fixed quantity. Thus, the money supply curve will be a vertical line, indicating that it is independent of interest rates.

The Supply Curve for Money and Interest Rates

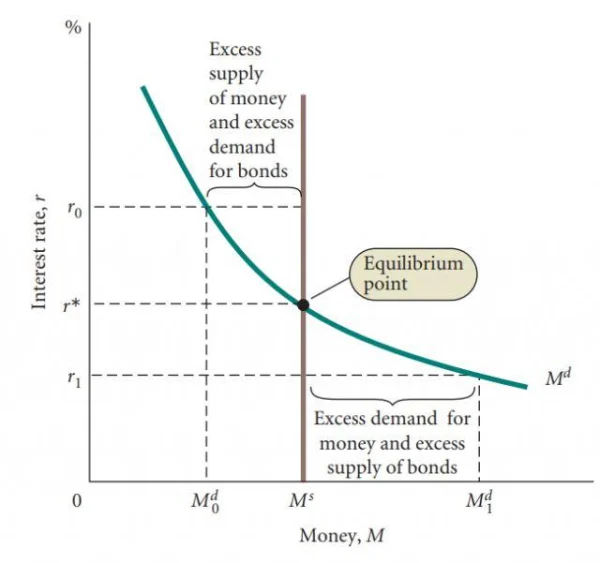

When we plot both the money supply and demand curves on the same graph, they intersect at a unique point known as the equilibrium interest rate. Typically, market interest rates tend to gravitate toward this equilibrium point, where the amount of money that individuals wish to hold equals the total money supply in the economy.

When the interest rate is lower than the equilibrium rate (such as at r1 in the diagram), money demand exceeds money supply. In this case, individuals will want to hold more cash, prompting them to sell bonds, which leads to a decline in bond prices and subsequently an increase in bond yields back to equilibrium.

Conversely, when the interest rate is higher than the equilibrium rate (such as at r0 in the diagram), money demand is less than money supply. People will be less inclined to hold cash and will purchase more bonds, leading to a decrease in bond yields and pushing the interest rate back toward equilibrium.

This rewritten article incorporates professional insights and specific examples in the field of finance and stock investment, reflecting an experienced perspective. Let me know if you need further modifications!

DLMvn > Glossary > Understanding Money Demand and Interest Rates

Expand Your Knowledge in This Area

Glossary

What is a Stock? Basic Steps to Start Investing in Stocks

Glossary

Central Bank: The Power Regulating The Economy

Glossary

What Is An Inverted Yield Curve?

Glossary

Federal Open Market Committee Meeting (FOMC Meeting)

Glossary

The Federal Reserve (FED), Monetary Policy, and the Stock Market

Glossary

Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs): An Overview